Take a look at your bookshelf. What do you see? Bindings, titles, paperbacks ...? No, I said take a look at the shelf. The furniture not the contents. It is not something I'd paid much attention to, but after reading The Book on the Bookshelf by Henry Petroski, I'm looking at the lines of steel and wood with new eyes.

His books is, put simply, a history of the bookshelf. Must be short, you might think, but the story is considerably longer and more complex than you'd think.

First, of course, came the scroll. Not, on the whole, terribly convenient. The Iliad would have filled a dozen rolls, "nearly 300 running feet of papyrus" in total. Which provides an explanation of why the separation of words by spaces did not become general until after the invention of printing; it would have added 30 feet to Homer.

The valuable scrolls had their own slip-cases, sets were usually kept in boxes "not unlike a modern hat box", while a "library" had a series of pigeonholes. But in one of those wonderful ancient/modern parallels, Seneca the Younger complained about the "evils of book-collecting" -:

"It is in the homes of the idlest men that you find the biggest libraries - range upon range of books, ceiling high. For nowadays a library is one of the essential fittings of a home, like a bathroom ... collected for mere show, to ornament the walls of the house."

I've read elsewhere that the Christian preference for the codex helped it defeat the pagan, scroll-based religion, but here is an earlier story. Papyrus was for many centuries the writing material of choice, but when Ptolemy Philadelphus in the second century BC forbid its export, Pliny's Natural History reports that King Eumenes II of the Greek Kingdom of Pergamun, who wanted to establish a grand library, instead ordered the preparation of sheepskins to be used instead. The material was called charta pergamena, which led to the word "parchment". (It had, however, been known earlier, if less used.) And parchment could be sewed to hold the codex together, which papyrus could not.)

In storage of codexes first came the books chest. It could be locked - frequently with multiple locks, and different monastery officials each had a separate key, so all had to jointly agree to get out a book, and witness its removal. Often it was set on a rack, so that the front edge was at a convenient height for resting a book on while reading. But if a book was being set out for regular reading, it would be placed on a slanted lectern - a word that comes from the Latin legere "to read.

The next step was an armarium, more or less a chest sitting on its end, with the "lid" forming the door, and shelves dividing it, each holding one book, with its cover, often highly decorated, facing out. There was a problem as these multiplied, however, because you couldn't put more and more into a room, as they would block each other's light, and the librarian couldn't keep a stern eye on his charges. So instead books started to be arranged on long, wide lecterns. For further security, and to ensure they stayed in place, each book was chained in its place on a lecturn. This avoided the need for complicated arrangements of keys and locks, allowing broader access to the books, and more books to be made available.

Chains were attached to a ring on the coverboard of the book, often near the clasp which, on the opposite side to the spine, held it closed. But, as all we booklovers know, the number of books you own inevitably multiplies and exceeds the storage place. (Had the 17 million books in the US Library of Congress in 1999 been so placed, they would require about 2,000 acres, or three square miles of floor space.)

Then came the stall system. Two facing lecterns were placed a little apart and a shelf run between them. Books could be placed on this, still chained to the original lecterns rail, but placed down on the lectern only when needed. Then after one line of stalls, why not two? If you feel like the story has been a long one thus far, and we've only just arrived at something looking like a bookshelf, well we're now in the late 16th century. Pretty recent really.

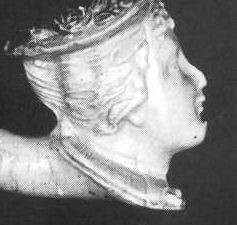

But remember these books were still chained, and the chain was attached to the side opposite the spine. So the spine went into the depths of the book stall - now increasingly called a press, with the pages facing outwards. As at the 16th-century library in Hereford Cathedral ...

As printing developed, and books became far less valuable, the chain started to become an unnecessary nuisance, and was dropped for the cheaper books, they were still placed this way, because that's what had always been done. But with more books, even the spaces under the lectern, or desk as it increasingly became, were utilised for storage. Here, books were vulnerable to kicks and scuffs. Turning them around, with spine outward, provided some protections.

So finally, in the 17th century, we've arrived at the bookshelf as we recognise it. But it isn't, Petroski makes clear, in any way inevitable. It is a wonderful lesson in the ways in which we think practices that are "natural", "obvious" and "the only way to do things" often aren't.

You sometimes feel that Petroski is living in another world - "modern" and "hat box" is not a phrase I'd be likely to form (don't think I've ever seen a hat box), and sometimes he gets bogged down in rambling philosophical debates, such as that about "which came first" of the standing or the sitting lectern. But this is a fascinating book, the product of a truly original mind. If you consider yourself a bibliophile, you should have it on your shelves.