A lot of what I read is about gender issues, sexuality and similar, and an email exchange off-blog recently made me think about why these are valuable beyond simply the information they contain. Studying these areas provides a continual reminder that other cultures, other times, other people don't see the world in the same way you do and make you realise the unthinking assumptions that underlie anyone's world view.

Looking at Lovemaking: Constructions of Sexuality in Roman Art 100BC - AD 250, by John R Clarke certainly does that. It examines artistic representations of sex in Roman art, rejecting in general a reliance on texts, invariably written by elite males, and tries to use the details in the art, its nature and distribution, to get at an understanding of how other Roman groups saw sex.

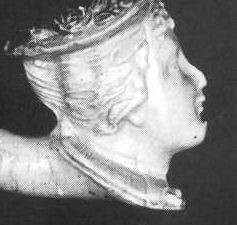

One possible reaction was laughter, although a very different laughter to the embarrassed titters of a school group when sex-ed comes around. So the famous Pompeii Priapus has an apotropaic function at the entrance to the passageway into the house, to ward off the Evil Eye.

Since a small penis was considered beautiful, a large penis, as with a dark skin, blonde hair, deformities and other departures from the Roman ideal, was a cause for mocking, powerful laughter. (For the Romans compassion for difference or disability was not an admirable characteristic.) ""Art from both the Hellenic and Roman period frequently represented dwarfs, hunchbacks, or people with enlarged heads; such use of malformations in art for the sake of comedy is quite common". (p. 238)

Talking about a similar figure from the Timgad Northwest Baths, of a macrophallic Ethiopian: "Levi points out that in antiquity people believed that atopia or unbecomingness dispelled the Evil Eye, ... as well as normal beings represented in indecent attitudes, making vulgar gestures or noises ... Laughter is the opposite pole of the anguish produced by the dark forces of evil". (p. 131)

Priapus is also seen often, for the same reason, at crossroads.

So that was perhaps the main reason for "unbecoming" depictions of lovemaking, a category that would not correspond in any way to our classifications, or indeed, as Clarke points out, our ideas of "explicitness" or "soft-core/hard-core". Priapus was "nothing core".

Clarke argues that the Suburban Baths at Pompeii, where containers for clothes left by customers were identified by a series of explicit little paintings, provide an escalating scale of Roman shock. Pretty bad was anything that affected the purity of the mouth, particularly for men. "It was the organ of speech and above all the organ of public oratory. Social interactions also focused on the clean mouth, since it was customary for social equals to kiss when greeting each other ... In invective literature, the worst possible insult is to accuse a man of fellating another man, and the worst possible threat against a man is that of forcing him to fellate someone." Even worse was providing the same service for a woman. (p. 224)

A male accepting penetration was even worse, although there was no shame in being the penetrator. (Much like in many Middle Eastern cultures today.) The most extreme painting in the baths has five participants combining all of these, supposed, on Clarke's reading, to provoke helpless laughter.

But sexual depictions could also have other readings. Clarke suggests that the paintings in many of the Pompeii villas, up to the richest, often mixed more or less indiscriminately with non-sexual images, were simply reading sexual art as part of the expected range in an educated, discerning collection. As the gift of Venus, sexual pleasure was something a rich person might expect to enjoy in abundance.

Even in the famous Pompeii Lupanar (brothel), he argues the depictions of sex, usually read as being indications of services offered, are actually depictions of luxurious aristocratic lovemaking in a place where nothing like that was on offer. "The profile of the sex-for-sale business that emerges is one of freedmen buying slaves (both male and female) specifically for use as prostitutes.... The range of prices for these prostitutes' sexual services varied from 2 asses (the cost of a cup of common wine) to 16 asses."

The paintings are also a reminder that the Romans had almost no concept of privacy as we understand it. Clarke argues that in the famous Warren Cup, the young servant boy looking out of the scene probably represents the viewer, but in other cases servants are shown in rooms where lovemaking is occurring, going about their business and ignoring the sex. He argues that this is again an indication of luxury - the servants, usually young and beautiful, adding to that.

This is not a very readable work (anyone looking for titillation will be seriously disappointed); the author is setting out a detailed academic arguments, but I found it well worth ploughing through, for the understanding it gives for ancient objects that are still treated with discomfort, disdain, and even disgust, in academic contexts that should know better.

****

I might note as a postscript that the book presents some lovely examples of Victorian utter misreadings, some of which persist until today. So a room with a painting of a couple on a bed on one side and on the other showing three women is interpretted as "on the right a woman consults a female panderer; on the left she gets her wish - a male prostitute. At best, this interpretation rests on flimsy visual evidence; at worst, it reveals Victorian notions that prostitution must be at the root of any representation of a man and woman enjoying sex." (p. 105)

Similar the House at IX, 5, 16 at Pompei... August Mau supposed that "the four erotic paintings of room ft (a fifth is destroyed) could be put only in a room of a building where sex was for sale. He implies that no decent person would have such pictures in his bedroom. Mau's construction of 'decency' for the Pompeian owner and his guests is, of course, highly suspect. As a 19th-century Christian gentleman of the Victorian period, Mau was the product of an acculturation with regard to sex that could find even the glimpse of a woman's ankles 'indecent'." (p. 178-9)

Scholarship since then has, I think, in general greatly improved, although I'm rather less confident about popular understanding.